I just came in from mowing my lawn, and pulling up a mess of matted, withered, crunchy and dry flower stalks in the beds. It’s almost fall, and though it hasn’t turned cold and STAYED cold yet, everything is in the process of turning crunchy and withered.

I could have let those splayed out viny dead plants stay there, and ultimately get covered up by the next season in line (in Northern Michigan, winter is long enough without tempting it too come early), but instead I tried to pull them up and clear the beds. Make them look a little more presentable, cleaned up, even … nice?

Or just … less dead?

And then I found myself remembering how, last night, while I cuddled with my 4yo and talked with him about all his many thoughts and wonderings, he looked at me with his stunning, blue – and suddenly wet – eyes and asked, “Ma, ah you goin’ to DIE?”

“Am I going to… die?” I asked, clarifying. His speech can be fast and garbled and hard to understand sometimes, after all.

But also because I needed a second.

He nodded “yes” slowly and intentionally.

“Ah you?” he asked, and put his hand on my chest.

I took a deep breath. I glanced at my husband, next to us in the bed. He sometimes zones out into his own little world of scrolling or listening to a podcast, but he was tuned in and paused as well.

You see, my kids know about my cancer diagnosis. And we don’t talk about it a LOT, as we’re still in the planning-for-my-treatment stage. Also, to them, I don’t appear sick or symptomatic, which probably makes it seem abstract. But we also know they need to understand what’s happening. So we’ve tried to give the kids some developmentally appropriate information. And to let them know they can ask us any questions they have.

So, apparently he had this question. With his little chubby hand, resting top of the tiny tumor that I can’t even feel.

“Well, someday – hopefully a long, long time from now – everyone will die. But even though I have this sickness, I don’t think it’s going to make me die. I have lots of doctors and helpers who are going to try to get all the cancer out of my body and make me feel all better.”

He listened, and nodded, and we snuggled for a few minutes more.

When he started talking again, it was about his beloved Crybabies toys and Youtube videos.

But my little guy and I talked about my Mom (his “grandma that he never met”) before. About her having died a long time ago. And one of his questions about her (“Why she die?”) was answered long ago with the words, “She had a sickness called Cancer.”

And now he knows I have cancer.

And he’s putting things together.

So as I was pulling those withered brown stems and leaves and shoving them into a composting bag, I too was putting things together.

I don’t think I’ll die.

My cancer was found early.

The tumor is tiny.

Herceptin is a “miracle drug” – according to my surgeon – that absolutely melts tumors.

A bilateral mastectomy (the path of I’ve chosen to take, when it FINALLY happens) will drive down chances of recurrence in a HUGE way.

There’s a great survival rate.

I don’t think I’ll die.

But on panicky, keyed-up nights where sleep eludes me and I become paralyzed in wakeful fear, the thought comes to my brain. I think about advanced directives I need to fill out. And risk. And these thoughts seek control, mastery, escape from my deep-seated worries and emotions. I think “What if my kids don’t have their mom? What if my husband doesn’t have his wife? Because … it kills me?”

In a moment of vulnerability, I told my friend this the other day and instantly, she said, “No. No. Don’t go there.” I could see her discomfort at the notion of my going there.

I assured her I don’t often, but with my family history – a mom who ultimately died from cancer – I can’t NOT go there, either.

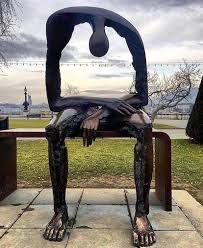

She wasn’t begrudging me the opportunity to speak my fears, but it got me thinking about how uncomfortable it is to talk about – and encounter – the possibility of death.

As I pulled up those weeds, I thought about how no one likes to imagine a youngish person dying. I mean, when kids and teens die, it seems like the ultimate injustice. All that potential – gone. But I’m supposed to get to live into my 80s or so, right? Maybe 90s with all our advances and life expectancies and well-being and all, right? Become old and (even more) shrunk and (even more) gray and (yes, even more) stubborn and unable to hear my husband speak so we’ll shout across the house at each other, right?

Right.

I found myself thinking back to last summer when having a cancer diagnosis wasn’t part of my reality. Though mine is quite a small family, we were gathered down in Hocking Hills, Ohio to celebrate the wedding of the oldest “kid” in the generation after mine.

Though there’s not many of us to gather, we aren’t a “family reunion” type of family. So this blessed event was basically serving as such, and we were recognizing that. With vaccine availability and life essentially back to normal after Covid, it was the first big wedding I’d been to.

My dad and his wife were there, as were my siblings, and my four cousins. A few of their kids were present, but it was actually a chance for Tim and I to escape without our brood in tow. My mom’s sisters and their spouses (my aunts and uncles) were also there.

My mom was the youngest of her sisters. With her gone almost 20 years now, today my Mom would be 80 years old. Which makes her sisters (mathing… mathing… computing…) now about 84 and 88. And their husbands … even older!

All things said, they get around, are sharp and continue to be mentally and physically active, as they are able. What a blessing!

And as we lightly expressed our joy of being together for the first time in too long, my cousin spoke up, “Well, the next time we’ll probably all be together again will be for a funeral!”

My sister and I looked at each other a quick wide-eyed glance. Later, my brother and I would pull each other aside, and say, “Wow. Did you HEAR that?”

I mean, she wasn’t wrong.

And no one is getting any younger.

But just the thought of admitting that death is coming – whether or not you know it because of a terminal diagnosis or if it comes without warning – is just inherently uncomfortable.

Like, if we speak it, it might happen.

It might come true.

And it will. Someday.

But we don’t want to tempt it, or invite it over too soon.

Like I told my 4yo, I hope it won’t be for a long long time. I have doctors and helpers and so many people who are going to help me to get through this and get better.

And even though mu aunts and uncles (and heck, my dad and his wife!) are advanced in age, and have led long and wonderful lives, I recoil at the thought of losing them. I hate thinking of the world without them in it.

Can’t we just… NOT go there? Please?

As I bagged a few more dead scraps of plants, I also found myself thinking about my internship placement from my second year of Clinicals when I was in school for counseling. I interviewed at a few different sites, but fell head over heels for a bereavement support program connected with a hospice. Luckily, the feeling was mutual and they became my placement.

I remember the asking me, in the interview, what drew me to them?

And while I thought about my own experiences with losing loved ones, I ultimately realized – for me – it was about how universal loss is.

We won’t all experience addiction, or homelessness. We won’t all personally know what living with schizophrenia or borderline personality disorder are like.

But NO ONE escapes losing someone they love, or care about.

Like it or not, sooner or later, we all experience losing someone and confront the finality of death.

And even though death and loss are inherently uncomfortable, I wanted to find a way to become someone who could become a little more … comfortable… with death.

Comfortable, how?

Well, we all grieve differently, but I wanted to learn how to confront it.

To me, this meant to not change the subject, but rather to talk about it. To use real words, and not euphemisms or vague references. To not sugarcoat it or theologize it. To speak aloud the names of people we’ve lost and miss. To feel the sadness and frustration and anger that comes with it. To grapple with our inability to fix or solve the problem of death.

That internship was a GIFT, man. It wasn’t easy. But it was also an honor to work with people, and talk about their loved ones, and their relationships – both good and bad parts – and to consider what legacy these loved ones had left for their people.

I find myself thinking about all these things as I look back at the past two weeks.

A friend died.

And though she had been sick, and struggling, it made no sense. I was blindsided when my husband called me with the news. It knocked the wind out of all of her loved ones.

The stories, the feelings, the questions – all so uncomfortable to feel and confront – erupted in the way only an unexpected loss like this can elicit.

It’s such a hard emotional road to walk.

We make plans. We dig through photos. We engage in rituals. We care for those impacted most closely, with food and offers of help and promises to show up.

We lean on each other, we share memories, we cry because the hole in our life feels so big and profound and so horrible.

We try to make sense of what can’t be fully understood.

And no one gets to avoid it, deny it, escape it.

So while I don’t want my 4yo (or any of my four kids) to fixate on the possibility of it or obsess about it or worry themselves into sleepless nights about it, I do want to talk about death.

Whether we’re young, or old.

Expecting in or not expecting it.

Sick or healthy.

Relieved about it or horrified by the possibility of losing everything we hold dear.

For better or for worse.

Talking about death is an uncomfortable, but so necessary, conversation to have. And to keep having, as understandings change and new questions emerge.

And yes, because I’ve long been avoiding it, I need to go read, and think about it, and fill out that dang advance directive.